“Stories That Empower” Podcast

Thursday, May 17th, 2018Terry did a podcast with Sean over at Libsyn. You can listen to her story here: Terry’s Story

Terry did a podcast with Sean over at Libsyn. You can listen to her story here: Terry’s Story

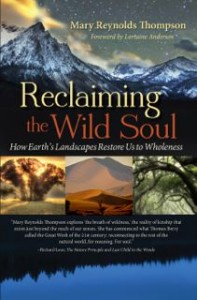

I am happy to announce that my good friend and colleague Mary Reynolds Thompson’s latest book Reclaiming the Wild Soul: How Earth’s Landscapes Restore Us to Wholeness is now available!!!

I am happy to announce that my good friend and colleague Mary Reynolds Thompson’s latest book Reclaiming the Wild Soul: How Earth’s Landscapes Restore Us to Wholeness is now available!!!

“Reclaiming the Wild Soul” is a must read for anyone looking for a joyous path to wholeness. Mary Reynolds Thompson’s superb book takes us back to our deep roots in nature where our dreams and destiny intertwine. Her book ignites the soul with the earth’s powerful wisdom and connects each of us to our deepest, wildest, wisest selves.”

— Terry

You can purchase a copy of Mary’s book here: http://www.amazon.com/Reclaiming-Wild-Soul-Landscapes-Wholeness/dp/1940468140

I was asked by Mary to share a story for her Wild Soul Story series. I can never resist telling a story and mine is about a healing from a pine tree! You can listen here: http://maryreynoldsthompson.com/terry-laszlo-gopadze-5/

I was asked by Mary to share a story for her Wild Soul Story series. I can never resist telling a story and mine is about a healing from a pine tree! You can listen here: http://maryreynoldsthompson.com/terry-laszlo-gopadze-5/

Mary reminds us that, “ A wild soul story requires you to leave the well-worn path and enter the dark and leafy terrain of your imagination. It communicates in the language of poetry, metaphor, and nature.”

You can watch Mary’s book trailer here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YCS_oWVbIjI&list=UUGHMYLdn1488aOY8XgsDJmQ

You can download your free Wild Soul Mandala and check out Mary’s schedule of workshops, readings and other events by visiting her website: http://maryreynoldsthompson.com/.

Each of us is here to discover our true Self,,,

that essentially we are spiritual beings

who have taken manifestation in physical form,,,

that we’re not human beings that have occasional spiritual experiences,,,

that we’re spiritual beings that have occasional human experiences.

-Deepak Chopra

Somewhere in the far reaches of my mind I hear her calling. Coming instantly out of an already light sleep, I am awake, alert, lucid. In soft cotton socks like cat’s paws, I make my way down the stairs and through the darkened kitchen to the doorway of her room. The thudding of my heart seems strong and powerful enough to sustain us both.

The buglight, mounted just outside her window, throws a beam of harsh yellow light across her bed, coloring the room in illness. It silhouettes the high cheekbones of her thin, wrinkled face, draining away any trace of animation that might have been there. She lies motionless on her back, eyes closed, face tilted upward toward heaven… or maybe the ceiling. This unnatural state of inertia has shrouded her sleep for many months. Standing in the stillness, I search for the courage to move closer. Not tonight, please not tonight.

As I lean down to listen for a breath and to watch for the rise of her chest, my own breath is cut short in a fear-induced synchronicity with hers. I’m here Gram, I heard you, I’m here. And then, cutting into the silence, a sharp intake of air, the rise and fall of her chest, and she gives me back my breath, deep inhalations of relief. Thank you, Gram. Thank you for breathing and for giving me one more day to make amends.

Pulling a chair over, I sit by her head and stroke her hair. How easy it is to be kind in the darkness where our demons lurk to remind us of the evil we ignore in the brilliance of the morning sun. There is no escape from this dance of cruelty I do. With every spoon I bring to her lips, with every trip to the bathroom, every adjusted pillow or change in position, I am a little less gentle, a little less caring, a little more angry, a little more weary. I dance on in a frenzied song of resentment, building to a crescendo of guilt until finally, the sun begins to set and all is quiet again.

As I sit here by her frail, sleeping form, I long to crawl in under the covers and curl up next to her like I did as a child. But my child-self will not find what she is looking for. She will find, instead, adult anger and the shadow of something left behind.

It’s so hot. My nightgown clings to my damp body. I can’t breathe. I try but I am suddenly racked with a deep, raspy, uncontrollable cough. From somewhere in the darkness I hear her voice.

“It’s okay darling, cough it up. I’ll stay with you. I’ll stay right here.” I am nine years old, she’s close and I’m safe. Then suddenly the coughing begins again and my adult self reaches out to comfort her in a painful role reversal. Where did you go Gram? She forgot my name today as she spoke of those from sixty years ago. The pictures in her mind are sharp, clear, and alive with color as she recalls a young girl on a long-ago voyage bravely stepping into a new and foreign land. Seven siblings wait patiently in Europe for the time when they too can take that journey. A younger brother and sister join her in America, as five others, seven nieces and nephews, and both parents are sent to Auschwitz. There are four survivors. And as they arrive, one by one, the indelible marks of Hitler’s camps are etched as deeply and permanently in her heart as they are on the delicate flesh of her sister’s arms.

I am enraptured as much by her voice as by the story it brings forth. At twelve I could hardly wait for winter break and the chance to hear that voice again. Rushing into her six-story Bronx building, I welcomed the familiar clang of apartment doors as their echoes rang out in the empty corridors. Curled in a chair in a corner of her small, safe kitchen, reflections of my girlhood spilling forth, I shared all my secrets and then begged for hers.

What are you secrets now, Gram? The pictures in my mind are clear and vibrant too, memories rich in color as the fuzzy blacks and whites of today slowly fade into washed out shades of grey. Was it just last night that she called out in her sleep? Last week? Two hours ago? Two months? My spirit aches with the pain of her disease while hers remains bright and strong in spite of it.

She had an extraordinary way of instilling confidence at my most vulnerable times. At nine, a metal cart stuffed with groceries between us, I walked with her toward the tiny concession stand she ran in the middle of an enormous golf course. The open expanse of land provided no protection from the oppressive city heat or the golf balls that flew across the sky without warning. My fear of being hit with one nearly paralyzed me until the steady, familiar rhythm of her voice assured me that she wouldn’t allow it to happen. An instant later the wind shifted and a small white blur flew past my ear and landed in the basket just inches away. Adrenaline pumping and heart pounding, I was indignant. “See Gram. I told you! I told you!” She turned slowly to face me and putting her hand gently on my shoulder, she asked, “Did I let it hit you?”

Standing, I bend down to kiss the top of her head.

“Goodnight Gram,” I whisper, “See you in the morning.”

The words lie heavy on my tongue, resonating with the nakedness of the plea behind them. As I turn to go, she reaches for my hand in the darkness.

Looking up at me through eyes that have seen and endured so much, she says, “It’s not good to be sick. Get married soon so I can come to your wedding.”

“I will Gram, I will.”

As I utter the now familiar promise, a new and overwhelming significance embodies my words. A keen awareness of her need to be a part of this milestone shades the exchange with an unnatural sense of power. If I hold out on my promise, she’ll hold out on hers. As mind and body deteriorate, we continue to make promises and each day we struggle separately to keep them. When someone dies, we are told so often that it is okay to be angry and it’s okay to feel sad, yet we rarely hear those words when the person we are mourning is still alive.

Returning to the room above hers, I fall into another light sleep. In this dream state, she comes to me. I hear her in the hallway, and there she is at the top of the stairs on strong and sturdy legs. Her cheeks are plump and flushed with color and I am eager to unravel my thoughts on her like balls of yarn from a basket. We speak together with voices as unused as the legs she now stands on. The rightness of the situation, the certainty that we have achieved clarity in the midst of a haze, reminds us of who we are. We have returned to each other. Like an unfocused photograph, the clarity begins to fade as morning arrives and the day takes on the fuzzy edges of reality.

Making my way to her room with knots of tension forming in my shoulders, I am relieved to see her awake and animated, last night’s events temporarily forgotten in favor of the morning ritual over toast an coffee.

“Take me to the table, Darling. I want to tell you something while we eat.”

“Okay, Gram. Let’s get you into your chair first. Hold my arm. It’s O.K.; I’ve got you. There, that’s right. Now let’s brush your hair.”

“Take me to the table now, O.K. Honey?”

“Yes, Gram we’re on our way.”

“Last night I had a wonderful dream,” she says, “I was walking and I went upstairs. We had a nice talk. It was good to walk again.”

I look up from my paper, meeting her eyes with my own, “I had that dream too, Gram.”

I held my breath and prayed a lot but I knew she was slipping away. And I knew that I could no longer be what she needed nor could I be there when she went. She knew it too, so she waited until I left before she passed away. She would not be at my wedding and I would not marry soon enough for her. Broken promises, like jagged shards of glass, cut into me with the searing pain of injustice.

In dreams, our souls beckon each other, forming a bridge that illuminates the unspoken promises of our continued journey together in the spiritual realm.

It’s been nearly five years. I am not yet married but I continue to keep my promise. And she continues to keep hers. We walk together at night.

Deborah L Staunton holds a B.S. in Early Childhood Education, a B.A. in Theatre Arts and postgraduate credits in Creative Writing. She has pursued her passion for theatre, specifically, stage management and lighting design in New York, Virginia & Pennsylvania and has published articles in Stage Directions, The Sondheim Review, and Amateur Stage as well as contributing theatre reviews to a website called MyLeisureTime.com. She has also utilized her background in infant development by re-writing the child development materials for Harcourt Learning Direct and has published articles in Writers’ Journal and The Acorn. Promises Kept has won Honorable Mention in the EL Dorado Writer’s Guild writing contest and First Place for memoir in the Fiction Writer’s Journey. Deborah is working on a book-length memoir about her journey to become a mother after four miscarriages and has plans for a second one about her daughter’s special needs. She resides on Long Island with her husband Dominic and their children Sophie, six and Sam fourteen months.

by Cay Randall-May

“Within loss, God always weaves a lesson and whispers the promise of healing.”-Eleanor Roosevelt

“Within loss, God always weaves a lesson and whispers the promise of healing.”-Eleanor Roosevelt

Some people eat chili peppers; I paint them.

The idea came to me one December day, sixteen months after my twenty-seven year old son, Paul, took his own life. I was numb with shock after his passing and, although I continued to work at my ordinary tasks, my thoughts obsessed on my loss. My days were a nightmare as I relived the horror of the police call that told me he had died. The few fitful hours of sleep that I got each night were my only time to forget, but they were much too brief.

For the first year after his death, I lost my usual enthusiasm for painting and drawing. All I could visualize were the balloons that we released at Paul’s memorial as they carried my dreams for his life into the sky. In my imagination, the tiny specks would eventually explode, snagged by jagged clouds.

That’s why the first peppers I painted that December day were so hopeful. Through them I had found a potent symbol for my continuing grief process.” There were just two of them in that first painting. I composed them in jarring contrast to a turquoise background — the color of the Arizona afternoon sky. The menacing clouds that had overshadowed me for months had finally cleared.

In that painting, the top pepper is green and torn open all along its length to expose its seeds. It symbolizes my heart, filled with hope but forever damaged. Below is an intact red chili of equal size, representing the internal combustion engine of creativity. I didn’t consciously begin this painting by choosing this symbology; it just flowed, felt right. So I followed my feelings.

More pepper paintings came in quick succession. I didn’t want to stop painting them. Sometimes I would start the next painting before completing the one before. To date, I have painted nineteen in this series, which I call “A Passion for Peppers,” and they continue to fill my imagination.

They document my healing as I move through profound grief, the pain of my son’s death catalyzing my process. I now realize that my emotions were partially numbed after my parents’ divorce, my own failed first marriage, and many other losses. What passed for happiness for most of my adult life had always a flat, gray feeling to it. I had been depressed for a long time without knowing it.

My son’s tragic decision made me examine my own will to live. My grief hurt; it burned within me, just like my stomach burns when I eat hot peppers. There was no relief from this constant emotional and physical pain except prayer, which I believe led me to more help.

One day in a bookstore, I came across a copy of “The Grief Recovery Handbook” by John James and Russell Friedman. The authors suggested working through feelings of loss with a partner, which I did. Soon after, I was given another answer to prayer. Someone told me about a Survivors of Suicide support group. Here I could talk with others every week. They truly understood my pain because they, too, had felt it. I learned that others who had lost loved ones to suicide struggled with the will to go on living.

The more I talked out my feelings, the more I wanted to paint peppers: yellow, red, orange, green of all possible sizes and shapes. I turned on cheerful, Latin music and danced as I painted. Each picture became more rhythmic, more alive. Eventually I included people in my paintings. First a woman with a pepper for her mouth suggested how I felt when I talked out my sorrow. It hurt, but it was essential. Next I painted a young, strong man with a pepper tattoo on his arm that proclaimed, “I love peppers.” He symbolized my own willingness to openly discuss my process with others. At the same time, I began to write articles on suicide awareness and became a volunteer public speaker.

Anyone who regularly eats peppers builds up a tolerance for capsicum, the chemical that gives them heat. People who work through their sorrows, who really taste their feelings, also become stronger. A friend emailed me this anonymous wisdom: “A strong woman has faith that she is strong enough for the journey, but a woman of strength has faith that it is in the journey that she will become strong.”

I realize that my journey through grief will be life-long, but it will make life more real. We do not need to feel to live, but if we feel, we can’t avoid living.

When someone first told me that every loss leaves us with a gift, I thought they were out of touch with the reality of my situation. How could my son’s death hold any gifts for me other than aching loneliness, guilt, and remorse? The “shoulds,” the “maybes,” and the “whys” tore at my soul. I was certain I could never receive any other gift. That was before the peppers.

Now I know otherwise. Paul’s death presented me with a choice. I can truly feel, or I can go totally numb. Every day, I renew my choice to awaken my heart through positive prayer. I don’t pray for my situation to be changed. It never will be. I will always miss my son and occasionally think that I see his face, recognize his stride in the silhouette of a stranger, or hear his voice saying, “Hi, Mom.”

Instead, I pray to feel life and to give others the courage to feel life. Without a doubt, my pepper pictures will be just kitchen decoration to some who see them, but to those who understand my journey, they will speak of renewed faith, hope, and joy.

Cay Randall-May

–read Cay’s bio here

![]()

“A woman is like a bag of tea:

“A woman is like a bag of tea:

You never know how strong she is

until she gets in hot water.”

-Eleanor Roosevelt

“Hello!” I called out as I set my bag down. I had just finished work and was emotionally and physically drained. The weeks behind me had been hard, but I knew what was to come would be much worse.

“We’re in here,” called out my older sister, Nadalea, from the bathroom in my mother’s apartment. I made my way down the hallway to the bathroom door and stared in horror. Nadalea was shaving our little sister’s head. Ali was now completely bald.

“It kept falling out in chunks,” Ali said, “so I decided to just shave it.”

I had known she was going to lose her hair, but not yet – not today. A week ago she had had long, curly hair that cascaded halfway down her back. To help her adjust to losing it, she cut it, and for fun, had dyed it red.

Now there was nothing. (more…)